install.packages("tidyverse")

install.packages("infer")Handling data using RStudio

Exercise 4

Welcome to RStudio

Launch RStudio. It should detect your R installation automatically, but if not, a window will open asking you to select it. If R does not appear here, I suggest you restart your computer first.

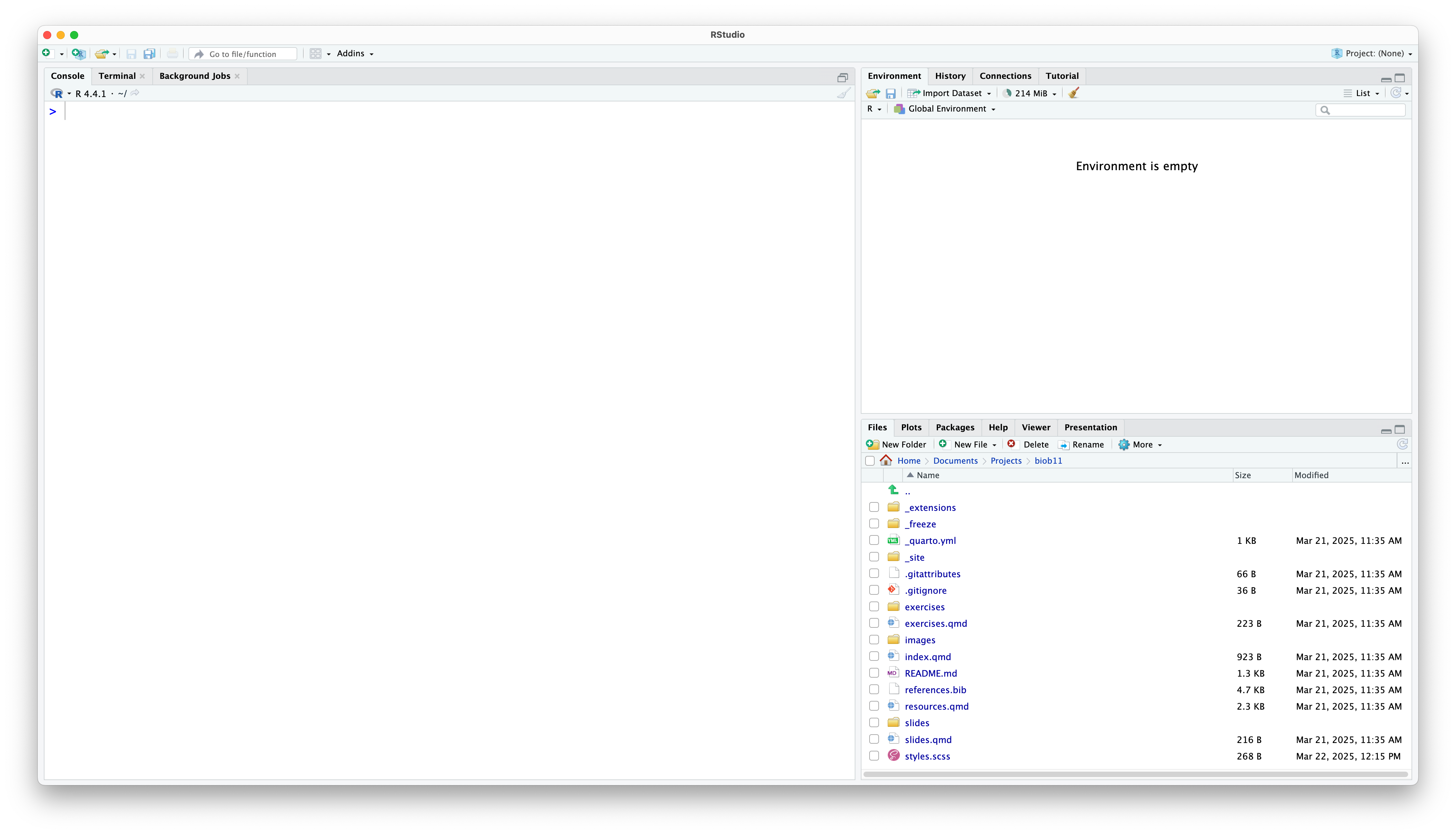

You should be met by a scene that looks like this:

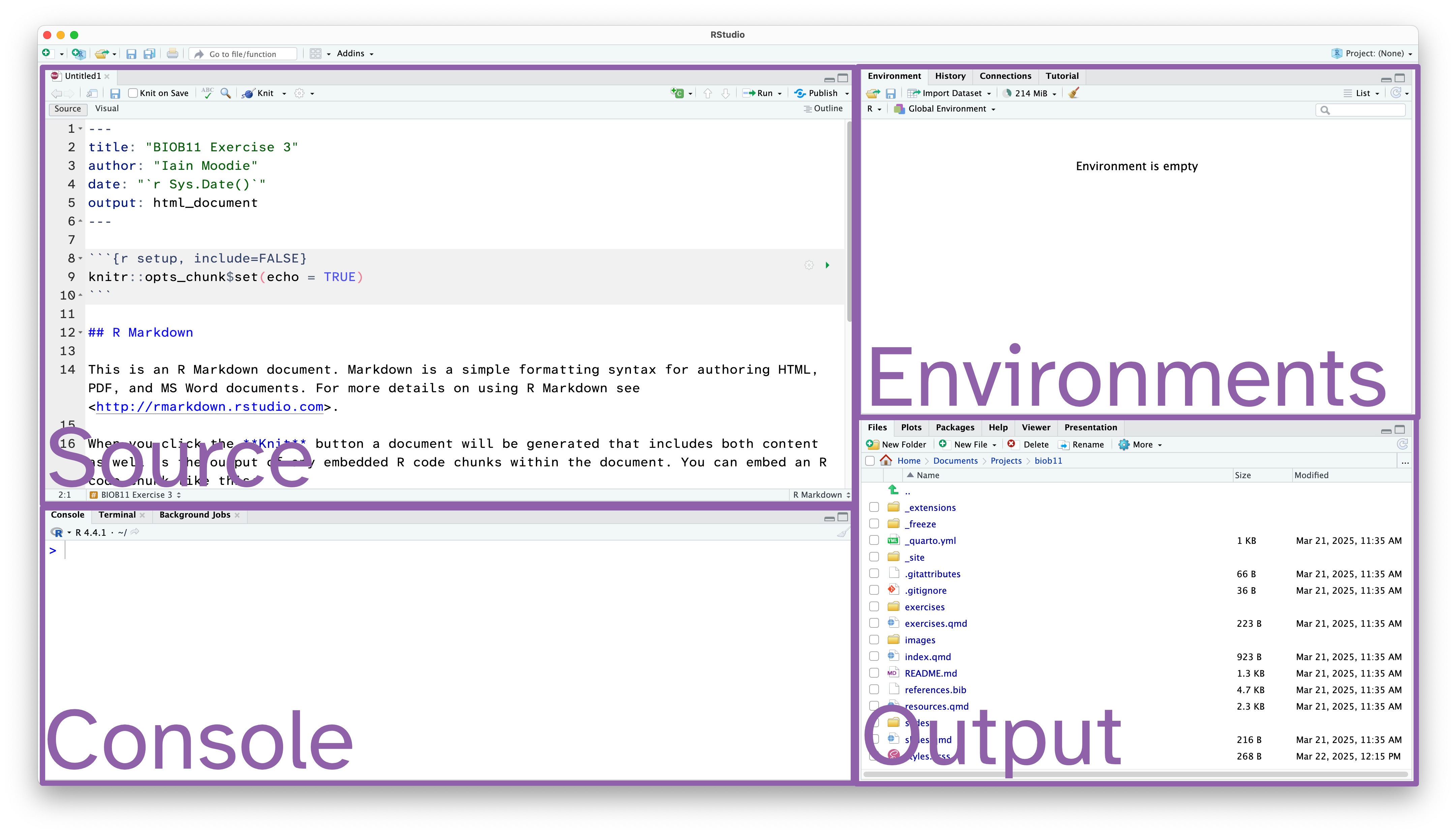

Rstudio is designed around a four panel layout. Currently you can see three of them. To reveal the fourth, go to File -> New file -> R markdown... This will open an RMarkdown document, which is a form of coding “notebook”, where you can mix text, images and code in the same document. We will use these sorts of documents extensively in this course. Give your document a title like “BIOB11 Exercise 4”. You can put your name for author, and leave the rest as default for now. Click OK. Now your window should look something like this:

- Source: This is where we edit code related documents. Anything you want to be able to save should be written here.

- Console: the console is where R lives. This is where any command you write in the source pane and run will be sent to be executed.

- Environments: this panel shows you objects loaded into R. For example, if you were to assign a value to an object (e.g.

x <- 1), then it would appear here. - Output: this panel has many functions, but is commonly used to navigate files, show plots, show a rendered RMarkdown file or to read the R help documentation.

RMarkdown

RMarkdown is a file format for making dynamic documents with R. It combines plain text with embedded R code chunks that are run when the document is rendered, allowing you to include results and your R code directly in the document. This makes it a powerful tool for creating reproducible analyses, which are extremely important in science.

The RMarkdown document you opened has some example text and code. An RMarkdown document consists of three main parts:

YAML Header: This section, enclosed by

---at the beginning and end, contains metadata about the document, such as the title, author, date, and output format.Text: You can write plain text using Markdown syntax to format it. Markdown is a lightweight markup language with plain text formatting syntax, which is easy to read and write.

Code Chunks: These are sections of R code enclosed by triple backticks and

{r}. You can click the green arrow to run all the code in a code chunk, or run each line of code using the Run button, or by usingCtrl+Enter(Windows) or Cmd+Enter (macOS)When the document is rendered, the code is executed, and the results are included in the output.

Notice at the top left of the Source panel, there are two buttons: Source and Visual. These allow you to switch betwee two views of the RMarkdown document. The Source view is what you are looking at, and it is the raw text document. You can also use the Visual view, which allows you to work in a WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) view, similar to Microsoft Office or other text editors. This “renders” your markdown code for you while you write. It also gives you a series of menus to help you format text, which means you do not need to learn how to write markdown code (although it is extremely simple, and you likely know some already).

Which ever view you prefer (and you can switch as often as you like), the code part stays the same. It is primarily there for editing the text around your code.

Important settings

Before we go any further, we need to change some default settings in RStudio.

Go to Tools -> Global Settings, then:

- Go to the General tab.

- Un-tick “Restore .RData into workspace at startup”

- Set “Save workspace to RData on exit:” to Never.

- Go to the Code tab

- Tick “Use native pipe operator, l> (requires R 4.1+)”

- Go to the RMarkdown tab

- Un-tick “Show output inline for all R Markdown documents”

While we are here, if you wanted to change the font size or theme, you can do that in the Appearance tab.

RStudio also has screenreader support. You can enable that in the Accessibility tab.

Working directory

I strongly recommend you create a folder where you save all the work you do as part of this course. I also recommend you make this folder in a part of your computer that is not being synced with a cloud service (iCloud, OneDrive, Google Drive, Dropbox, etc). These services can cause issues with RStudio. You can always back up your work at the end of a session.

Within your new course folder, I also want you to make a new folder for each exercise we do. This will make it very easy for you to stay organsied and submit work you do to me for feedback. It also makes your code reproducible by simply sending someone the contents of the folder in question. For example, this is exercise 4, so my main folder might be called biob11, and within that folder I might make a folder called exercise_4.

We now want to set our working directory to this biob11/exercise_4 folder. A working directory is the directory (folder) in a file system where a user is currently working. It is the default location where all your R code will be executed and where files are read from or written to unless specified otherwise. To set the working directory using RStudio, go to Session -> Set working directory -> Choose directory, then navigate to the folder you just made for this exercise. You should do this at the start of each exercise.

Notice that now in your Output pane, in the files tab, you can see the contents of your folder (which is probably nothing currently). Let’s change that.

Saving your document

Let’s save this example RMarkdown document that RStudio has made for us. You do that exactly how you might expect. Go to File -> Save, or use the floppy disc icon. Ensure you save it in your working directory with a descriptive name (e.g. exercise_4.Rmd). The file should have appeared in your Output pane, with the extension .Rmd.

Let’s move onto working with some data!

Data handling, plotting and analysis in R

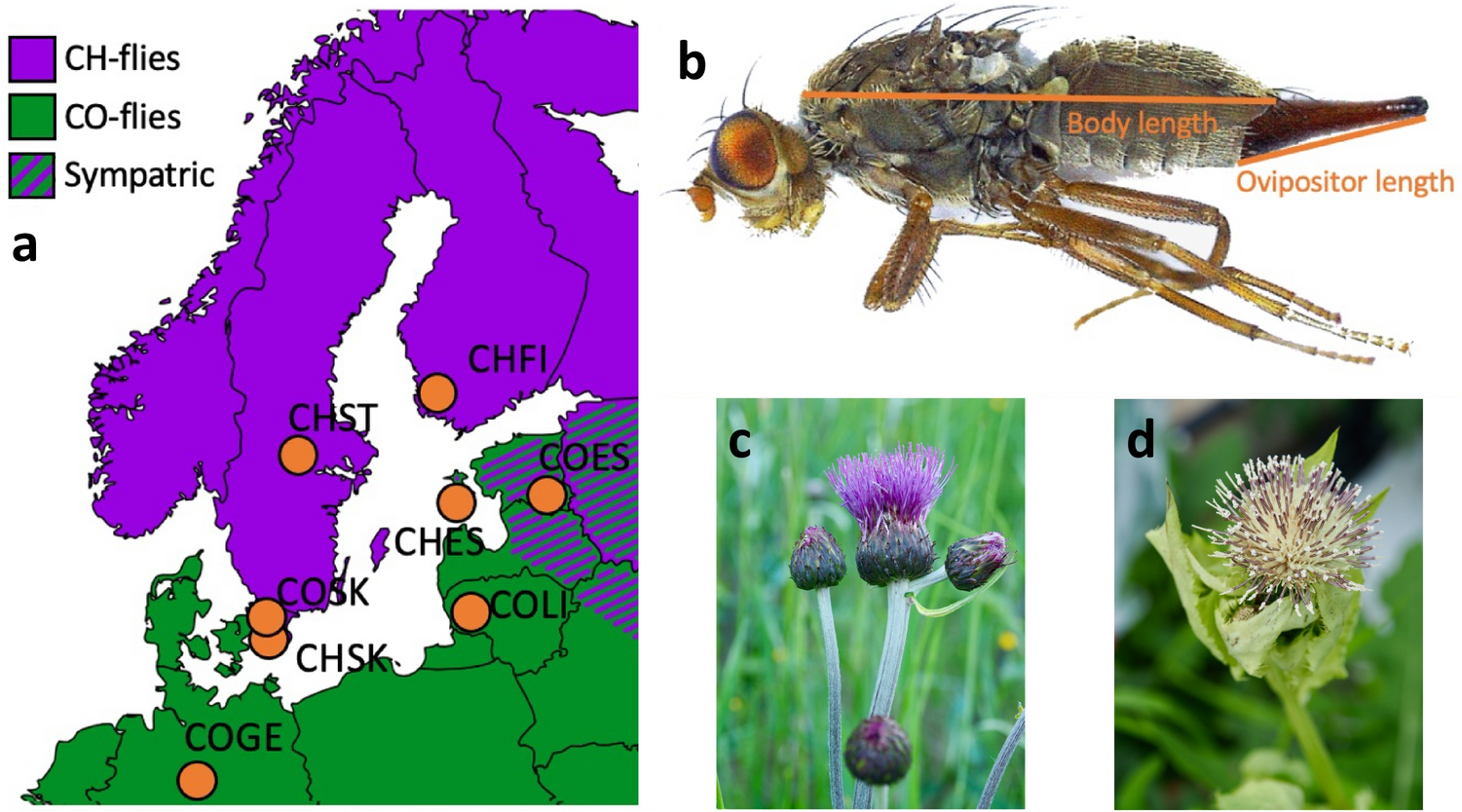

Today we will work with a dataset called tephritis_phenotype.csv. The dataset comes from a study conducted at Lund University by Nilsson et al. (2022).

The dataset describes morphological measurements of the dipteran Tephritis conura. This species has specialised to utilise two different host plants (

host_plant), Cirsium heterophyllum and C. oleraceum, and thereby formed stable host races. Individuals of both host races were collected in both sympatry (where both Cirsium heterophyllum and C. oleraceum host plants co-occur) and allopatry (where only one Cirsium species occurs) (patry) from eight different populations in northern Europe (region) from both sides of the Baltic sea (baltic). Individuals were measured after having been hatched in a common lab environment. One female and one male (sex) from each bud was measured. The authors took magnified photographs of each individual, and of the wings of each individual.

Measured traits included wing length (

wing_length_mm), wing width (wing_width_mm), melanised percentage cover (melanized_percent), body length (body_length_mm) and ovipositor length (ovipositor_length_mm). Body length and wing measurements were collected by measuring images digitally. Wing melanisation was measured using an automated script, which quantified how many pixels of the wing was melanised.

You can download the dataset here.

Once downloaded, you should move it to your working directory folder for this exercise before continuing.

Setting up the RMarkdown document

We will work with the RMarkdown file we generated at the start (that I called exercise_4.Rmd).

First, we should delete all the code and text that RStudio automatically generated, except the YAML header (the text at the start between the ---). You can do that as you would expect in any other text editor. Now we have our blank RMarkdown file, let’s get started.

Installing R packages

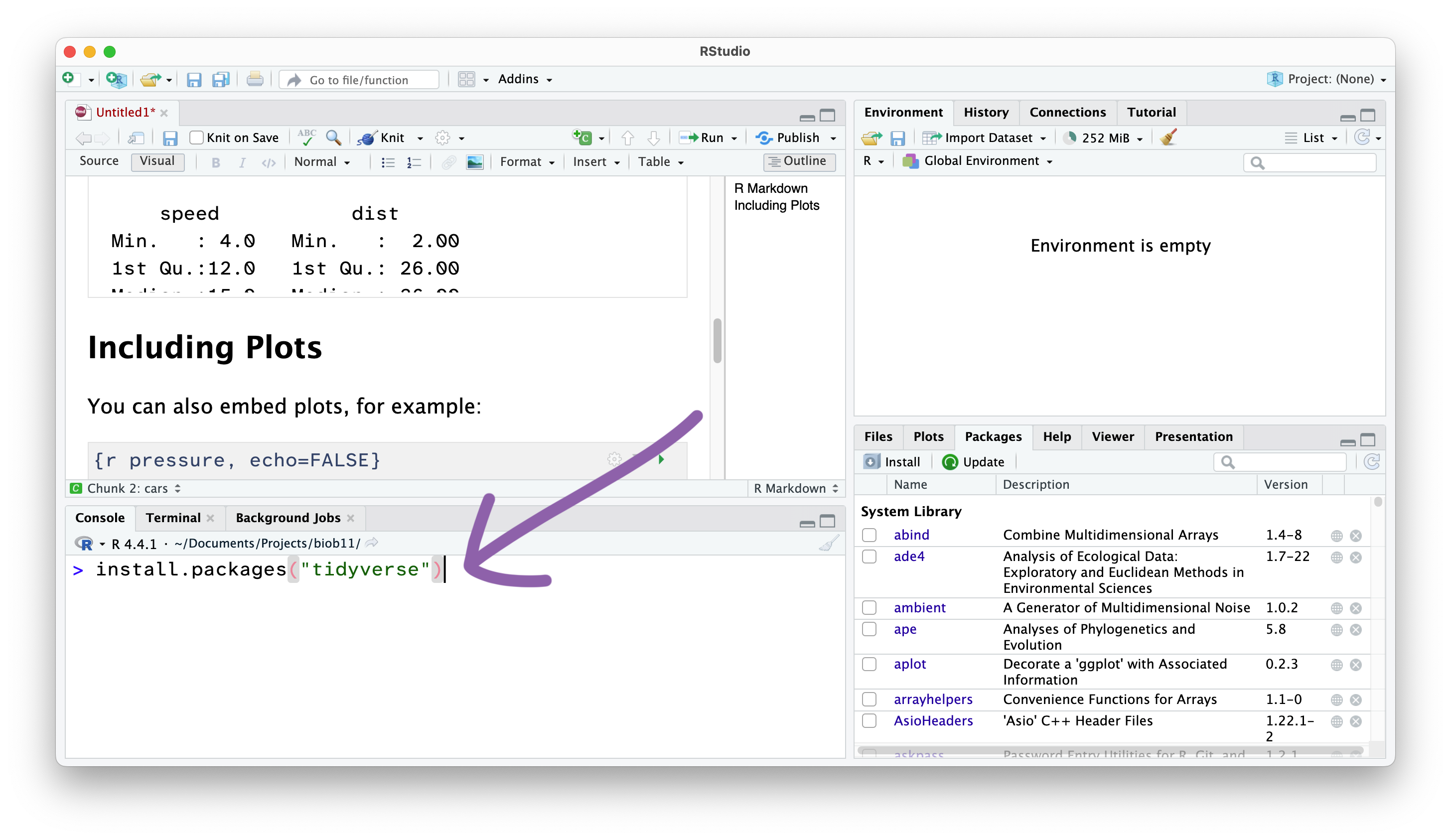

In this exercise, we will use the tidyverse package, and the infer package. To install them you need to use the install.packages() function. Since we only need to do this once per computer, we should run this function directly in the Console panel.

Type or copy the install function into the console, and press enter to run:

From now on, we won’t write things directly in the Console, and instead write code in the RMarkdown document in the Source panel, which we then “Run” and send the Console.

Creating code cells

Code cells are where we write code in an RMarkdown document. This allows use to write normal text outside these sections.

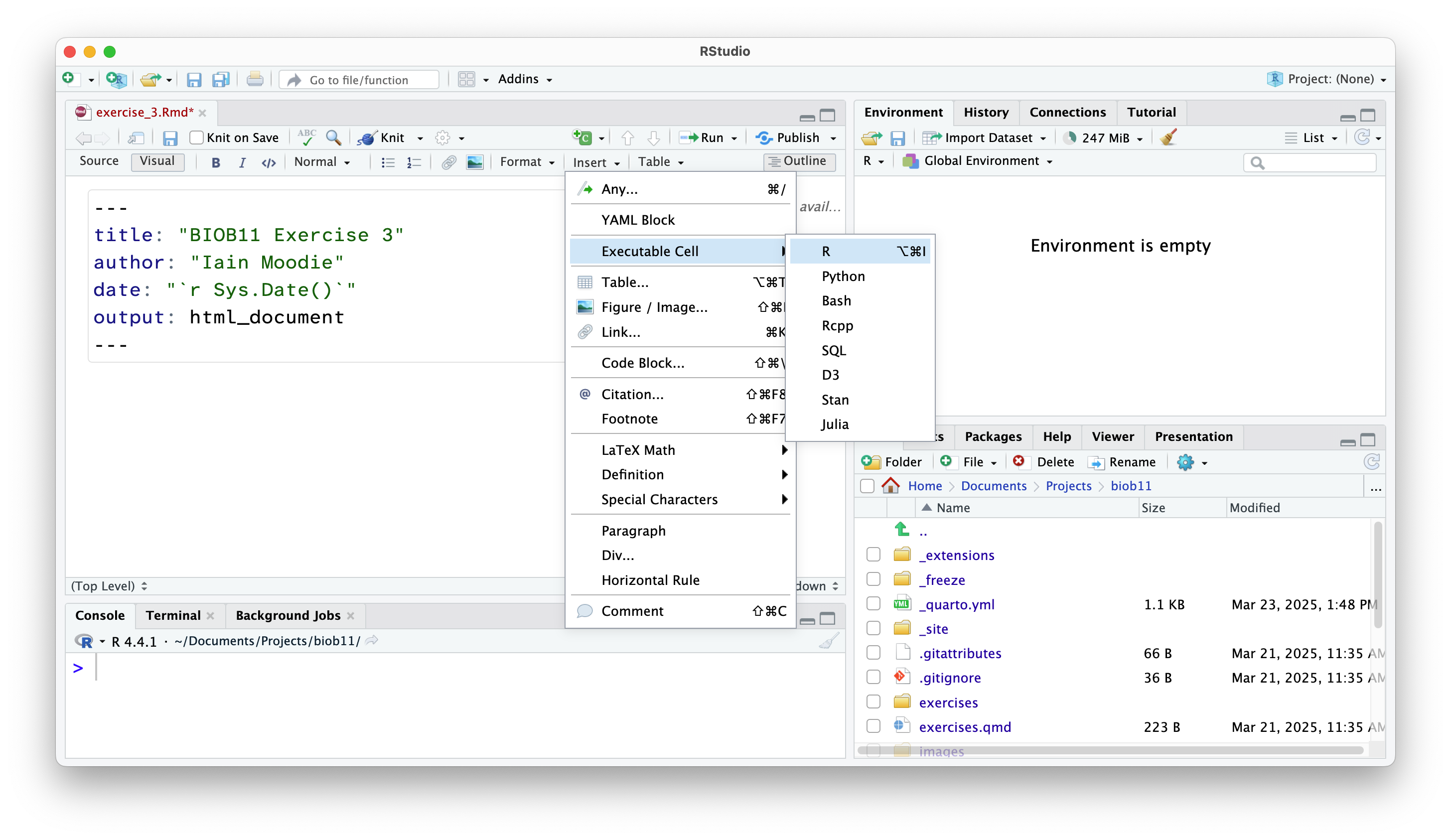

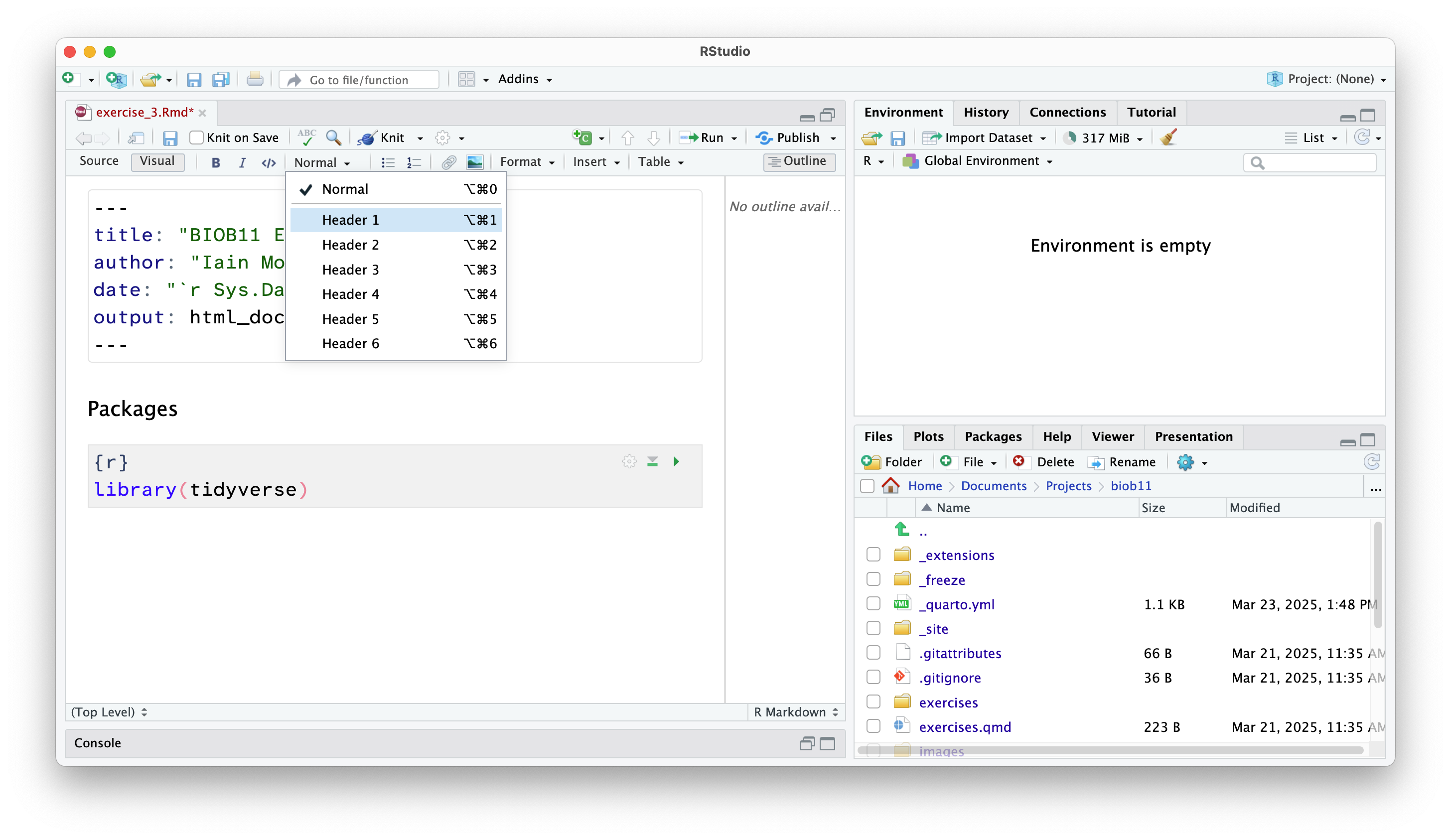

In your Source panel, in the RMarkdown document, add a R code cell.

In both views, you can also use the shortcut Shift-Alt-I or Shift-Command-I.

Loading R packages

After installing an R package, we need to load it into our current R environment. We use the library() function to do that. Since we need this code to run every time we come back to this RMarkdown document, we should write it in the document. R code should always be executed “top to bottom”, so this bit of code should come right at the start.

Inside that code cell you just made, use the library() function to load the tidyverse and infer packages:

(To run code in the Source panel, you can click on the line you want to run, and then press the “Run” button. Or you can also use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+Enter or Cmd+Return.)

library(tidyverse)

library(infer)If that worked, you will get a message that reads something similar to:

── Attaching core tidyverse packages ──────────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

✔ dplyr 1.1.4 ✔ readr 2.1.5

✔ forcats 1.0.0 ✔ stringr 1.5.1

✔ ggplot2 3.5.1 ✔ tibble 3.2.1

✔ lubridate 1.9.3 ✔ tidyr 1.3.1

✔ purrr 1.0.2

── Conflicts ────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errorsThis message tells us which packages were loaded by the tidyverse package, and which functions from base R (the functions that come with R by default) have been overwritten by the tidyverse packages. Not all packages produce a message when they are loaded (for example, infer did not).

Adding headings and text

Anywhere outside a code cell you can write normal text. In this course, you might find it helpful to write yourself notes alongside your code, so that you can come back to your notes during other exercises, the exam (open book), the group project, or later in your studies.

Along side normal text, you can structure an RMarkdown document using headings.

I leave it up to you to decide how and when to use headings and text.

Importing data into R

We will now load the tephritis_phenotype.csv data file that you downloaded earlier. A .csv file is a file that stores information in a table-like format with Comma Separated Values. A typical .csv file will look something like this:

species,height,n_flowers

persica,1.2,12

persica,1.5,18

banksiae,2.4,3

banksiae,1.7,8.csv files are especially suited to storing data that can be used across a wide variety of programmes, as everything is stored as plain text (unlike an .xlsx file from Microsoft Excel, for example).

Make another code cell.

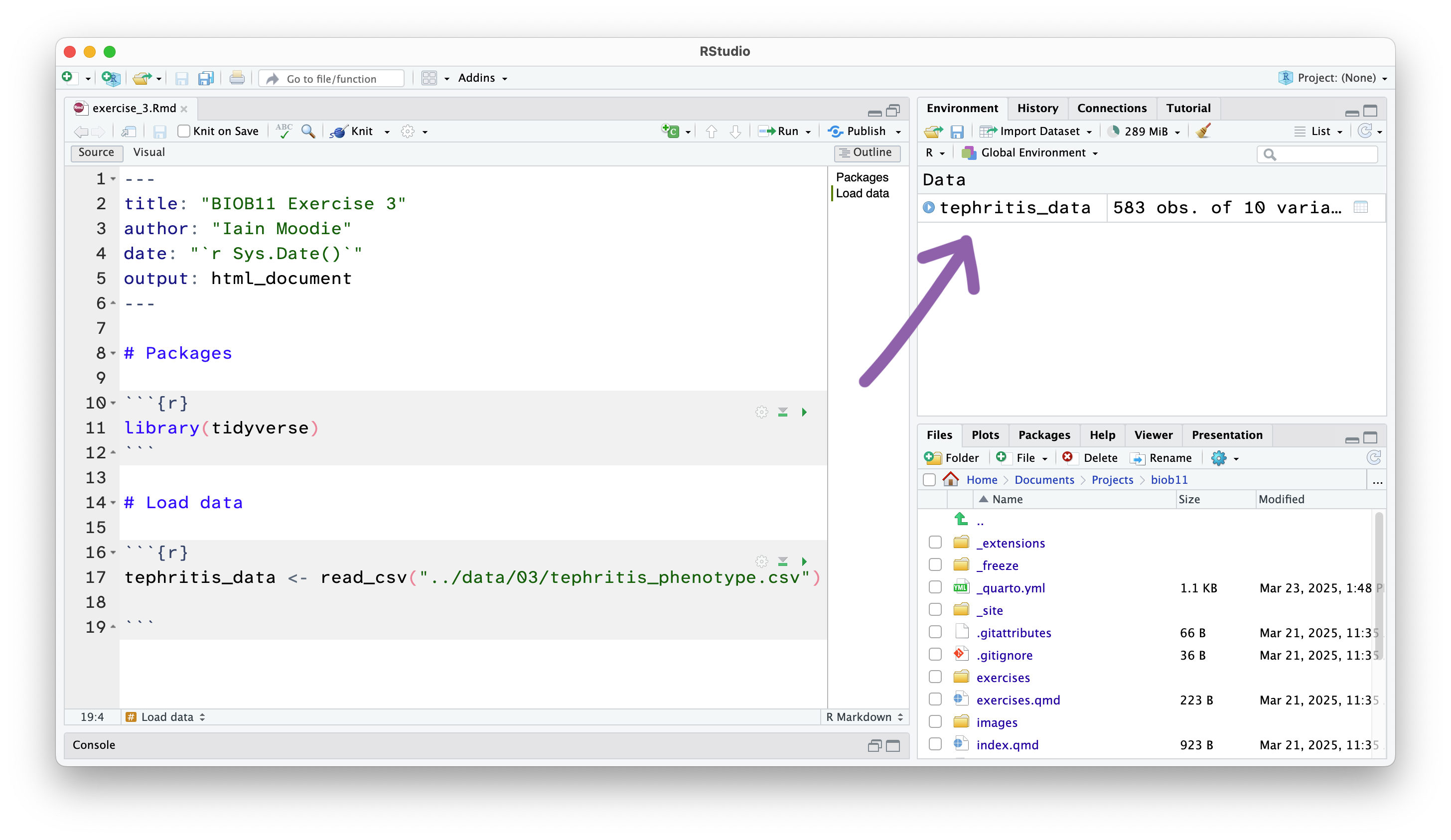

Load the tephritis_phenotype.csv data file using the read_csv() function and assign it to an object named tephritis_data.

1tephritis_data <- read_csv("tephritis_phenotype.csv")- 1

- Be sure to use quote marks around the file name.

If that worked, you should get the following message with some information about the data:

Rows: 583 Columns: 10

── Column specification ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Delimiter: ","

chr (5): region, host_plant, patry, sex, baltic

dbl (5): body_length_mm, ovipositor_length_mm, wing_length_mm, wing_width_mm...

ℹ Use `spec()` to retrieve the full column specification for this data.

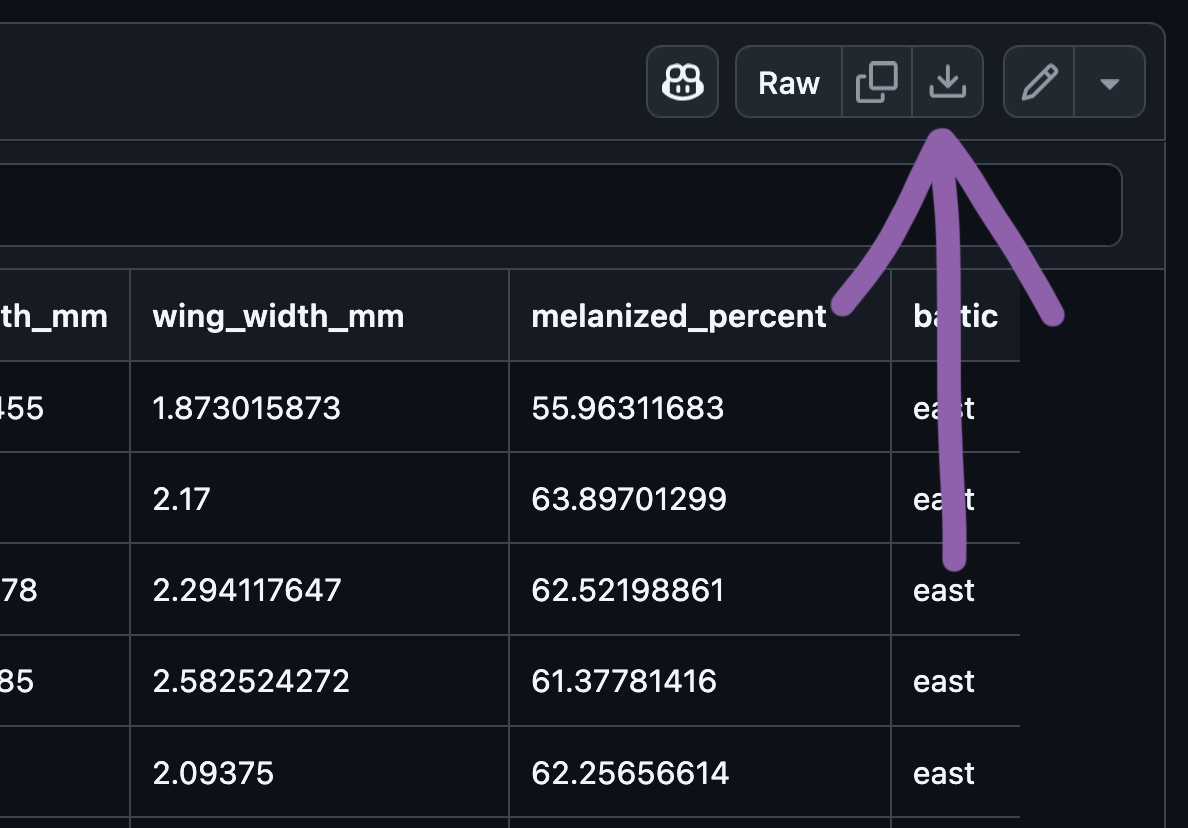

ℹ Specify the column types or set `show_col_types = FALSE` to quiet this message.This has loaded a copy of the data from tephritis_phenotype.csv into R. Notice that the object tephritis_data has also appeared in the Environment panel.

Click on the object tephritis_data with your mouse. This will open the dataset using the RStudio function View() (which if you look in your console, you will see it has just run). This allows you to view the dataset as a table, like you would in a spreadsheet software like Microsoft Excel. Note however, there is no way to edit the data in this view. This is by design. Any editing of the data needs to be done in the RMarkdown document with code. That way, you can keep a record of any edits you make, without touching the original data file.

Exploring data

Let’s use a few more functions to get a better understanding of the dataset. You may remember these from Exercise 2. Make a new code cell, and write the following:

1print(tephritis_data)- 1

-

We can also just simply write

tephritis_datawithout the print statement, and we would get the same output.

We can also use glimpse() for an alternative view:

glimpse(tephritis_data)You can also use the summary() function:

summary(tephritis_data)In your RMarkdown document, using text below the code cell, answer the following questions:

- What is the unit of observation in this data set? In other words, what does each row represent?

- What populations (statistical use of the word) could we make inferences about using this data?

- What type of variable is:

regionhost_plantpatrysexbody_length_mmovipositor_length_mmwing_length_mmwing_width_mmmelanized_percentbaltic

- Are there any

NAvalues in the dataset? In which variable(s) and why might this be?

Cleaning data

Datasets can often be messy. People make mistakes entering data all the time. You should check this dataset for potential errors. For a reference, these flies are very small, less than 1 cm in size.

Make a new code cell for cleaning your data.

- Use the output of

summary()to help you check for potential errors. - You can also, as you did before, click on the object

tephritis_datain your Environment panel, and click on each variable header to sort it in different ways. - For any suspicious variables where you think there might be mistakes, a good first approach is to plot your data. Use code adapted from previous exercises to make histograms to check your data for potential mistakes.

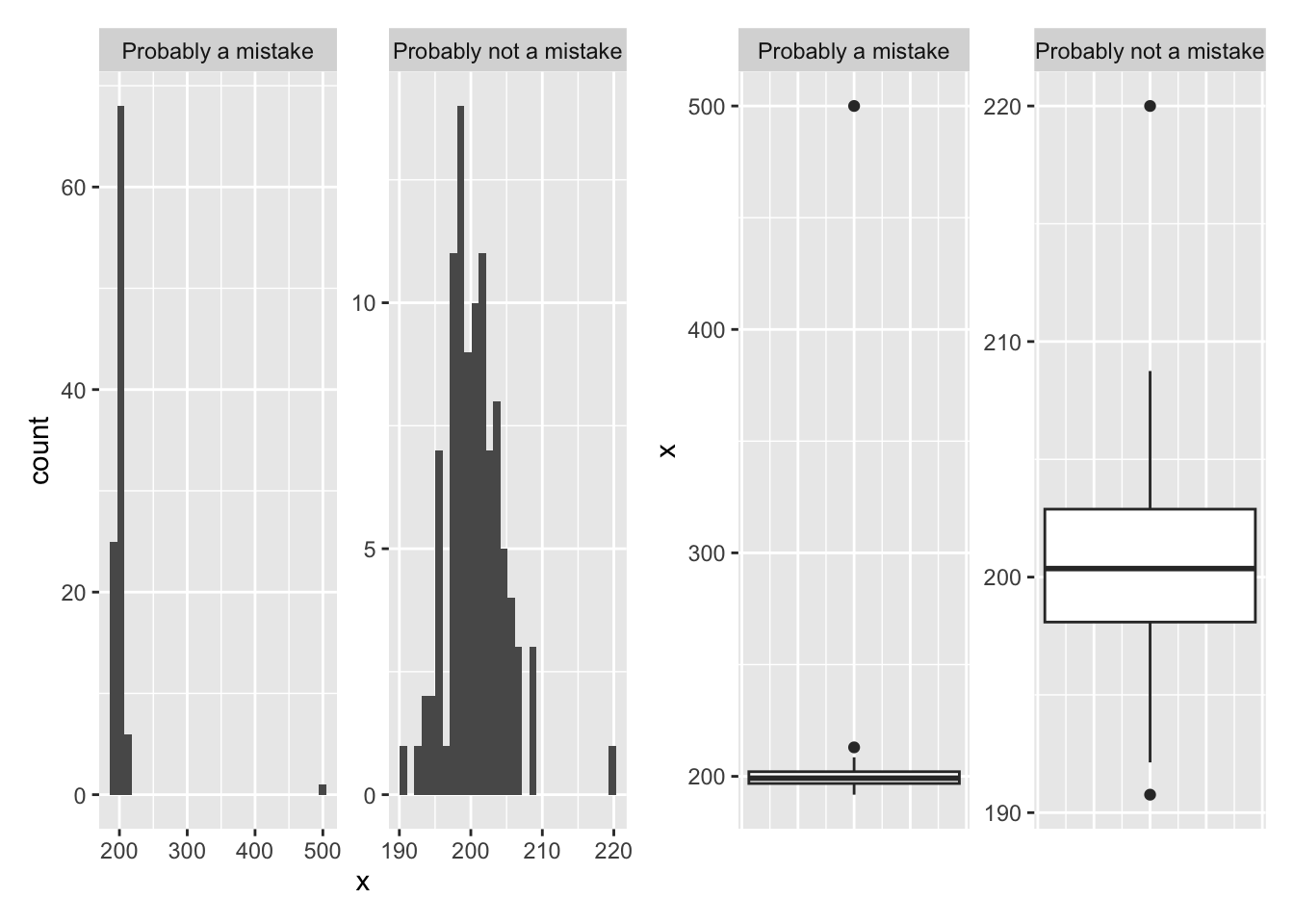

For example, in the histograms and box plots below both with an outlier point. Hopefully you can see the difference between an outlier (“Probably not a mistake”) and a real mistake (“Probably a mistake”). Remember, outliers are part of real data, and we should not remove them just because they are outliers. But they do have to be plausible to be kept.

Which variables do you think might have incorrectly entered data?

We will use a filter() function to inspect rows that contain improbably values. filter() let’s us write conditional statements (from Exercise 1) that only allow rows that meet those conditions to “filter” through. For example, we could use filter to see all rows where wing_length_mm is greater than our guess at what the maximum should be. Looking at the histogram of wing_length_mm, and with the knowledge that these flies are < 1 cm in size, adapt the following code to just show you the suspicious rows:

1tephritis_data |> filter(wing_length_mm > _____)- 1

-

This will only let though rows that have a

wing_length_mmgreater than>_____

What do you think? Do these values seem real, or are they probably mistakes? Use the code above to check your other suspicious variables. If you think these values are mistakes, then we need to get rid of them.

An easy way to do that is to use filter() again, but this time, to only allow rows that do have plausible values to “filter” through. That is, we can reverse the greater than > to a less than <. If we wanted to set a lower limit, we could that by using the & operator (from Exercise 1). We can also chain together filter() functions using pipes |> to clean up our dataset in one go. Adapt the code below to clean up the dataset:

- 1

-

I assigned the cleaned data to a new object, called

clean_data. - 2

-

You can add more

filter()functions as you wish.

Use the summary() function again, and make some plots to show that your data cleaning has had the desired effect.

Descriptive statistics

Make a new code cell. Inside it, write or adapt code from previous exercises to answer the following questions:

- What is the overall mean and standard deviation of:

body_length_mmovipositor_length_mmwing_length_mmwing_width_mm

- What are the

sexspecific means and standard deviations of:body_length_mmwing_length_mmwing_width_mm

- What are the

sexandhost_plantspecific means and standard deviations of:body_length_mmovipositor_length_mmwing_length_mmwing_width_mm

Hint: You will probably want to use the functions group_by() and summarise().

Exploratory plots

In a new code cell, use what you have learned in previous exercises to make some figures that explore the following relationships:

body_length_mmandsexovipositor_length_mmandhost_plantwing_length_mmandwing_width_mmandsex- The number of flies measured from each

regionandhost_plant

You should use the following geom_s at least once, but one plot can use multiple geom_s.

geom_point() geom_jitter() geom_boxplot() geom_violin() geom_bar()

To find out what they do, try using them, or search the helpfiles in the Outputs panel. You can also, for any function, search for the helpfile by writing ?function_name. E.g., if you wanted to know what geom_jitter() does, you could run the command ?geom_jitter, and the helpfile will open.

You can also consult the ggplot2 “cheatsheet” for help.

While making your plots, keep the following “best practises” in mind:

A good plot should:

- Show the data

- Make patterns in the data easy to see

- Represent magnitudes honestly

- Draw graphical elements clearly

ggplot2 allows for extensive customisation of your plots. For example, you might want to change the labels of the axis, or give your plot a title. You can do that using the labs() function:

ggplot(example_data, aes(x = variable_1, y = variable_2)) +

geom_points() +

labs(x = "Name of my x variable", y = "Name of my Y variable", title = "My awesome plot")You can also change the theme of your plot. ggplot2 has many built in themes. A full list can be found here. For my fake example, I could change the theme to theme_classic() like this:

ggplot(example_data, aes(x = variable_1, y = variable_2)) +

geom_points() +

theme_classic()Try it out on your plots. What theme do you prefer best?

In general, ggplot2 is a very widely used plotting package, so finding examples of what you want to do will not be hard. Use search engines, AI tools, the ggplot2 book, etc. If you see it on your plot, you can probably change it.

Data analysis

We will finish this exercise with an analysis similar to Exercise 2. Again, we will cover the theory behind these analyses more in depth during the lectures.

Make a new section in your R markdown file, with a new code cell(s). Make notes outside the code cells which you can refer back to at a later date.

Recall that the researchers measured flies that live in two different host plants. Although they are the same species, the use of these two different host plants functionally splits the species into two “host races”, that do not reproduce with each other.

Suppose the researchers have evidence to suggest that, before the species was split by colonizing these two host plants, the ancestral fly had a mean ovipositor length of 1.79 mm. The researchers want to know if either of the two host races have evolved a different ovipositor length, perhaps to better adapt to their new host plants.

For now, let’s focus on the heterophyllum host race.

We want to answer the question:

Is the mean ovipositor_length_mm in the heterophyllum host race different from 1.79 mm?

Hypotheses

From this research question:

- What population are we making inferences about?

- What is the null hypothesis?

- What is the alternative hypothesis?

Collecting data

As we are just interested in the flies that hatched from the heterophyllum host_plant, we should first make a subset of our data that is just the data we are going to use. Use filter() to create a dataset that only has:

- flies that hatched from the

heterophyllumhost_plant femalesexflies (as males do not have ovipositors)

The conditional statement == will be useful here.

Name this dataset something meaninful, like heterophyllum_data, or maybe something shorter if you prefer, like h_data.

Plotting data

Using this new dataframe, make a plot that illustrates your hypothesis.

Calculating the test statistic

First, we need to know what our test statistic, in this case the mean ovipositor_length_mm length we observe in our sample is. This is called our observed (test) statistic. To calculate this, we can use specify() and calculate(). First, we should pipe |> our filtered dataset into the specify() function. Inside specify(), we need to declare which variable we are interested in. In this case, we only have a response variable, as we are just working with the mean of one group. We then pipe |> that into calculate(), where we declare the name of our chosen test statistic. We save it as observed_mean_h, as we want to use it later to compare against a null distribution.

observed_mean_h <-

____________ |>

specify(response = ______) |>

calculate(stat = "______")

observed_mean_hSimulating data under the null hypothesis

Next we need a null distribution to compare with. First, we need to imagine that the null hypothesis is true. In this case, that mean ovipositor_length_mm == 1.79. To do that, we create a new dataset from our sample, where the mean ovipositor_length_mm == 1.79. We do that by using the difference between the mean in our sample 1.76 and mean we want to test against (1.79) to shift our data such that it is compatible with the null hypothesis. We then draw “bootstrap” replicates (sampling with replacement) from this new data and calculate our test statistic (mean) each time. Like in the example in exercise 2, we need to do this a lot of times to generate an appropriate null distribution (in this case, 10000 times).

null_dist_h <-

______ |>

specify(response = ______) |>

hypothesize(null = "point", mu = ______) |>

generate(reps = ______, type = "bootstrap") |>

calculate(stat = "______")Comparing our observed statistic to the null distribution

We can now use visualize() to show our null distribution, and the function shade_p_value() to show our observed statistic, and the proportion of the null distribution that is more extreme than our observed statistic. The direction you choose relates to your original alternative hypothesis.

- If your alternative hypothesis was that there would be a difference from 1.79 mm, but you didn’t specifiy if the evolved ovipositor would be longer or shorter (i.e., you didn’t predict a direction), then you should write

"two-sided". - If your alternative hypothesis was that the evolved ovipositor would be longer, then your hypothesis was one-sided, and you should write

"greater". - If your alternative hypothesis was that the evolved ovipositor would be shorter, then your hypothesis was one-sided, and you should write

"lesser".

null_dist_h |>

visualize() +

shade_p_value(observed_mean_h, direction = "______")We can also calculate from this what our “p-value” is. In this case, our p-value corresponds to the proportion of the null distribution that as extreme, or more extreme than our observed statistic. You can think of it being the probability we would observe data (i.e., collect our sample) if the null hypothesis was true. The closer it is to 0, the more confident we are that the null-hypothesis is not correct.

null_dist_h |>

get_p_value(obs_stat = observed_mean_h, direction = "______")Write a few sentence to describe the outcome of your test. In addition to the describing the test, also phrase your findings in terms that a friend who isn’t taking this class could understand (i.e., what do your findings suggest, related back to the original question).

Save your RMarkdown file!

Make sure you save your RMarkdown file regularly. If you want to turn it into a webpage similar to this one, you can click the “Knit” button, and it will appear in your Output panel.

Final exercise

You will now answer one (or more) of the following questions, by following the steps outlined above and in previous exercises. You should create a dataset that contains only the rows you are interested in, state your hypotheses, make plot(s), and use either a bootstrap (as above) or permute procedure to test your hypotheses. Write a small text at the end to describe your findings.

To decide which one you will work on, you are going to roll a virtual six sided die! Use this code to do it yourself:

cat("You will work on question:", sample(c(1,2,3,4,5,6), 1))- Do males have more dark patches on their wings than females?

- Do females have different length ovipositors in the two host races?

- Is the mean proportion of the female wing that is melanized greater than two-thirds?

- Do male flies from the east of the Baltic sea differ in size to flies from the west of the Baltic sea?

- Are female flies who live in sympatric populations bigger than female flies who live in allopatric populations?

- Is the median wing width greater than 2.1 mm in male flies?

Take-away points

At the end of this, you should have an idea how you would:

- Import a dataset into R using

read_csv(). - Check and clean the dataset of basic errors using

filter(). - Produce summary statistics of the dataset using

group_by()andsummarise(). - Produce illustrative plots of the dataset using

ggplot() - Compare a mean against a point value, or two means against each other.

Suggested extra reading:

- Ch. 2, 3 and 4 from Chester et al. (2025) cover importing, cleaning and plotting data with

tidyverse. - Ch. 7, 8 and 9 from Chester et al. (2025) cover hypothesis testing using randomisation in detail.

- Ch. 15 and 16 of Duthie (2025) cover probability and the central limit theorum, which we will cover soon.

- Part 7 of 7 of this video course covers what a p-value is very clearly.