install.packages("tidyverse")

install.packages("infer")Exercise 1: Data analysis using R

Welcome to RStudio

Just like you would any other program on your computer, open RStudio (not R!).

It should detect your R installation automatically, but if not, a window will open asking you to select it. If R does not appear here, I suggest you restart your computer first.

You should be met by a scene that looks like this:

Important settings

Before we go any further, we need to change some default settings in RStudio. If you know what you are doing and don’t like these suggestions, feel free to ignore them. If this is your first time using RStudio, then please follow them carefully. It will make following along easier.

Go to Tools -> Global Settings, then:

- Go to the General tab.

- Un-tick “Restore .RData into workspace at startup”

- Set “Save workspace to RData on exit:” to Never.

- Go to the Code tab

- Tick “Use native pipe operator, l> (requires R 4.1+)”

- Go to the RMarkdown tab

- Un-tick “Show output inline for all R Markdown documents”

While we are here, if you wanted to change the font size or theme, you can do that in the Appearance tab. RStudio also has screenreader support. You can enable that in the Accessibility tab.

Great, now that’s done, let’s move on.

RStudio layout

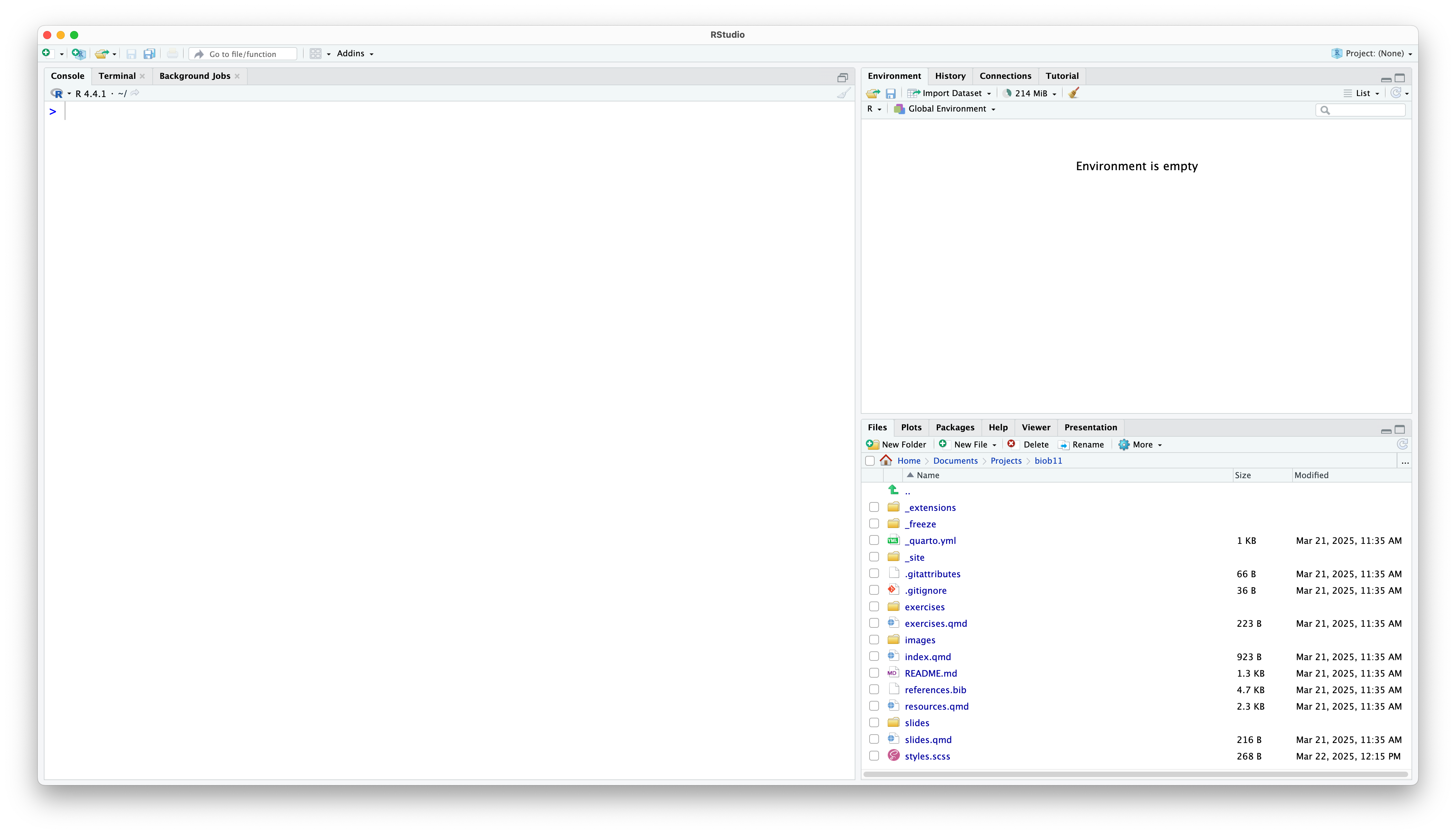

Rstudio is designed around a four panel layout. Currently you can see three of them. Follow the instructions to open an RMarkdown document, which will also reveal the fourth panel.

Go to File -> New file -> R markdown…

This will open a new window and you will be prompted to fill in some details about your new RMarkdown document.

- Give your document a title, such as

"BIOC13 Exercise Session 1". - Write your name as the author.

- Leave the rest of the options as default for now, and click OK.

This will open the RMarkdown document with some example text and code. If you followed the Getting familiar with R set of execises, you’re already familiar with Rmarkdown documents, as that page behaves exactly like one! They allow you to mix code “chunks” with text and images. Sort of like a powerful word document. We will use RMarkdown documents exclusively in this course.

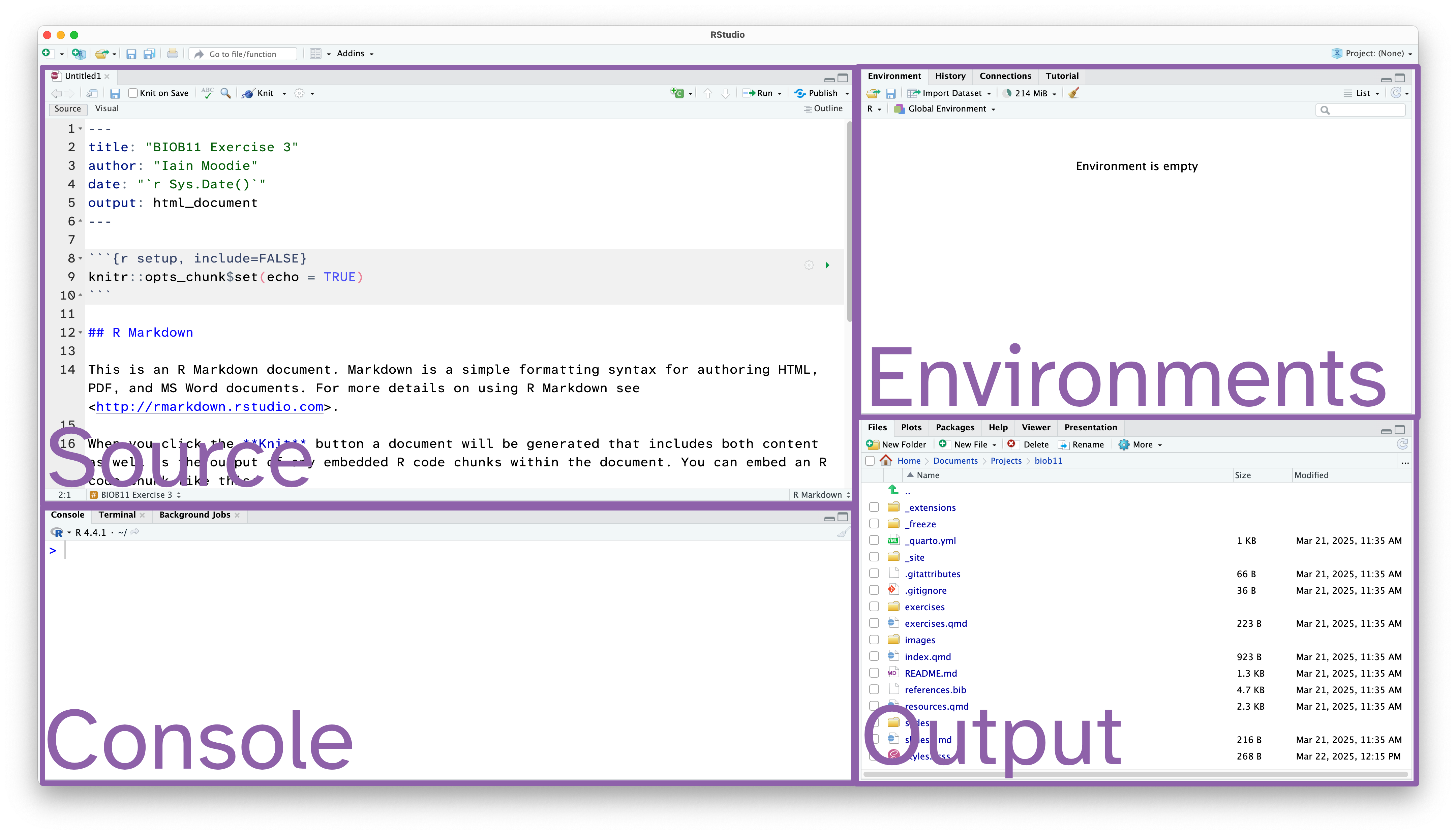

Your screen should look like the screenshot below. Note we now have four panels.

- Source: This is where we edit code related documents. Anything you want to be able to save should be written here.

- Console: the console is where R lives. This is where any command you write in the source pane and run will be sent to be executed.

- Environments: this panel shows you objects loaded into R. For example, if you were to assign a value to an object (e.g.

x <- 1), then it would appear here. - Output: this panel has many functions, but is commonly used to navigate files, show plots, show a rendered RMarkdown file or to read the R help documentation.

RMarkdown

RMarkdown is a file format for making dynamic documents with R. It combines plain text with embedded R code chunks that are run when the document is rendered, allowing you to include results and your R code directly in the document. This makes it a powerful tool for creating reproducible analyses, which are extremely important in science.

The RMarkdown document you opened has some example text and code. An RMarkdown document consists of three main parts:

YAML Header: This section, enclosed by

---at the beginning and end, contains metadata about the document, such as the title, author, date, and output format.Text: You can write plain text using Markdown syntax to format it. Markdown is a lightweight markup language with plain text formatting syntax, which is easy to read and write.

Code Chunks: These are sections of R code enclosed by triple backticks and

{r}. You can click the green arrow to run all the code in a code chunk, or run each line of code using the Run button, or by usingCtrl+Enter(Windows) or Cmd+Enter (macOS)When the document is rendered, the code is executed, and the results are included in the output.

Notice at the top left of the Source panel, there are two buttons: Source and Visual. These allow you to switch betwee two views of the RMarkdown document. The Source view is what you are looking at, and it is the raw text document. You can also use the Visual view, which allows you to work in a WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) view, similar to Microsoft Office or other text editors. This “renders” your markdown code for you while you write. It also gives you a series of menus to help you format text, which means you do not need to learn how to write markdown code (although it is extremely simple, and you likely know some already).

Use the toggle to see the document in both views. Which ever view you prefer (and you can switch as often as you like), the code part stays the same. It is primarily there for editing the text around your code.

Working directory

I strongly recommend you create a folder where you save all the work you do as part of this section of the course. I also recommend you make this folder in a part of your computer that is not being synced with a cloud service (iCloud, OneDrive, Google Drive, Dropbox, etc). These services can cause issues with RStudio. You can always back up your work at the end of a session.

Generally this is easier outside of RStudio.

- Make a folder for the statistics section of BIOC13.

- Make a folder within that folder for this exercise.

For example, this is exercise 1, so my main folder might be called bioc13, and within that folder I might make a folder called exercise_1.

You should make a new folder for each exercise we do. This will make it easy for you to stay organsied and submit work you do to me for feedback. It also makes your code reproducible by simply sending someone the contents of the folder in question.

We now want to set our working directory to this bioc13/exercise_1 folder. A working directory is the directory (folder) in a file system where a user is currently working. It is the default location where all your R code will be executed and where files are read from or written to unless specified otherwise.

Within RStudio go to Session -> Set working directory -> Choose directory, then navigate to the folder you just made for this exercise.

Notice that now in your Output pane, in the files tab, you can see the contents of your folder (which is probably nothing currently). Let’s change that.

Saving your document

Let’s save this example RMarkdown document that RStudio has made for us. You do that exactly how you might expect.

Go to File -> Save, or use the floppy disc icon. Ensure you save it in your working directory with a descriptive name (e.g. exercise_1.Rmd).

The file should have appeared in your Output pane, with the extension .Rmd.

Let’s move onto working with some data!

A walkthrough analysis

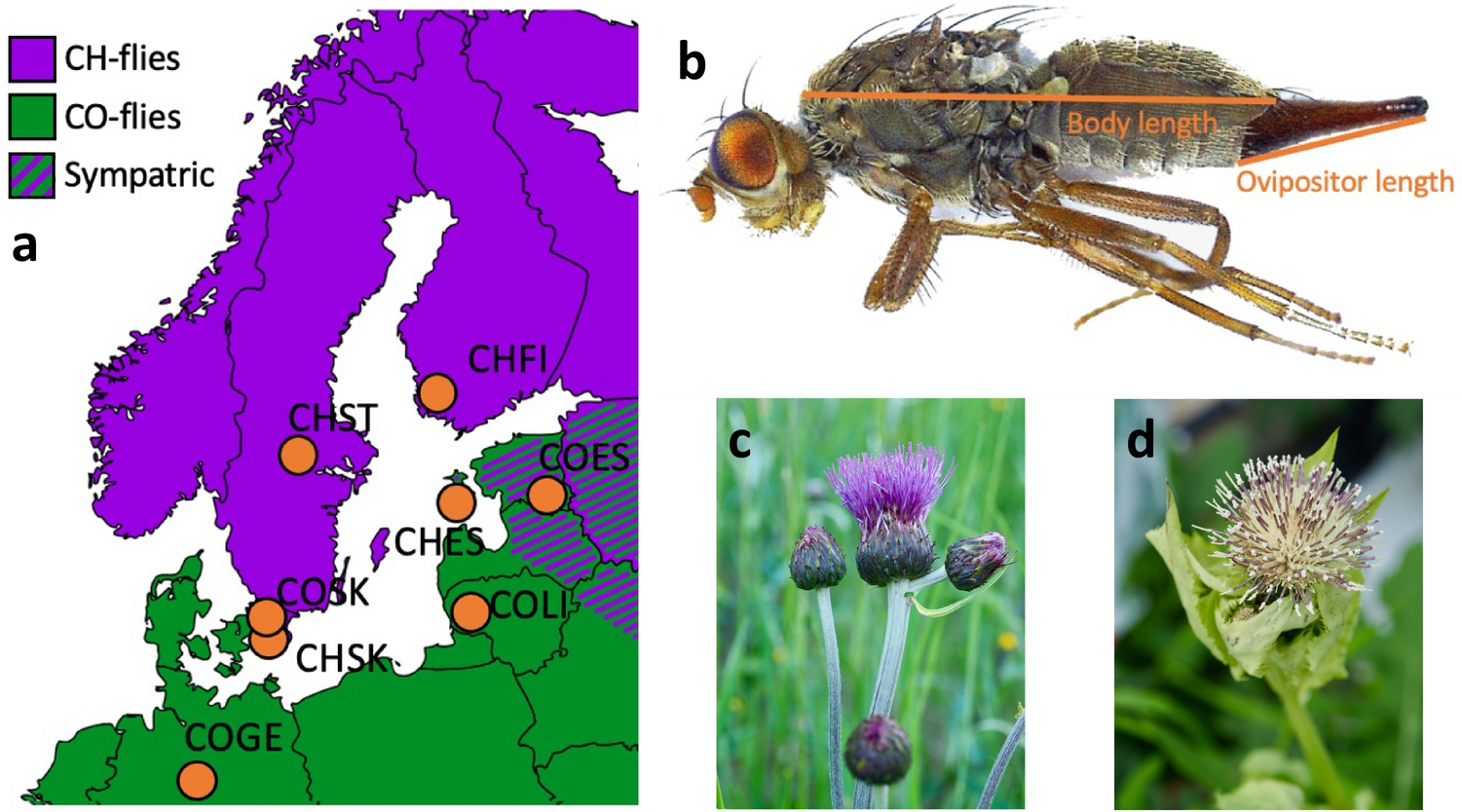

Today we will work with a dataset called tephritis_phenotype.csv. The dataset comes from a study conducted at Lund University by Nilsson et al. (2022).

Background

The dataset describes morphological measurements (lengths, widths of different body parts) of the fly Tephritis conura. This species has specialised to utilise two different host plants (host_plant), Cirsium heterophyllum and C. oleraceum, and formed stable “host races”. Individuals of both host races were collected in both sympatry (where both Cirsium heterophyllum and C. oleraceum host plants co-occur) and allopatry (where only one Cirsium species occurs) (patry) from eight different populations in northern Europe (region) from both sides of the Baltic sea (baltic). Individuals were measured after having been hatched in a common lab environment. One female and one male (sex) from each bud was measured. The authors took magnified photographs of each individual, and of the wings of each individual.

Measured traits included the length of a wing (wing_length_mm), the width of a wing (wing_width_mm), the amount of the wing that was melanised (melanized_percent), the length of the body (body_length_mm) and the length of the ovipositor (ovipositor_length_mm).

Getting everything setup

Before we conduct the analysis, we need to download the dataset and move it to our working directory.

You can download the dataset called tephritis_phenotype.csv from here.

Once downloaded, you should move it to your working directory folder for this exercise before continuing.

Next, let’s clean up our document.

Using the RMarkdown file we generated at the start (that I called exercise_1.Rmd):

- Delete all the code and text that RStudio automatically generated, except the YAML header (the text at the start between the

---). You can do that as you would expect in any other text editor.

Now we have our blank RMarkdown file, let’s get started.

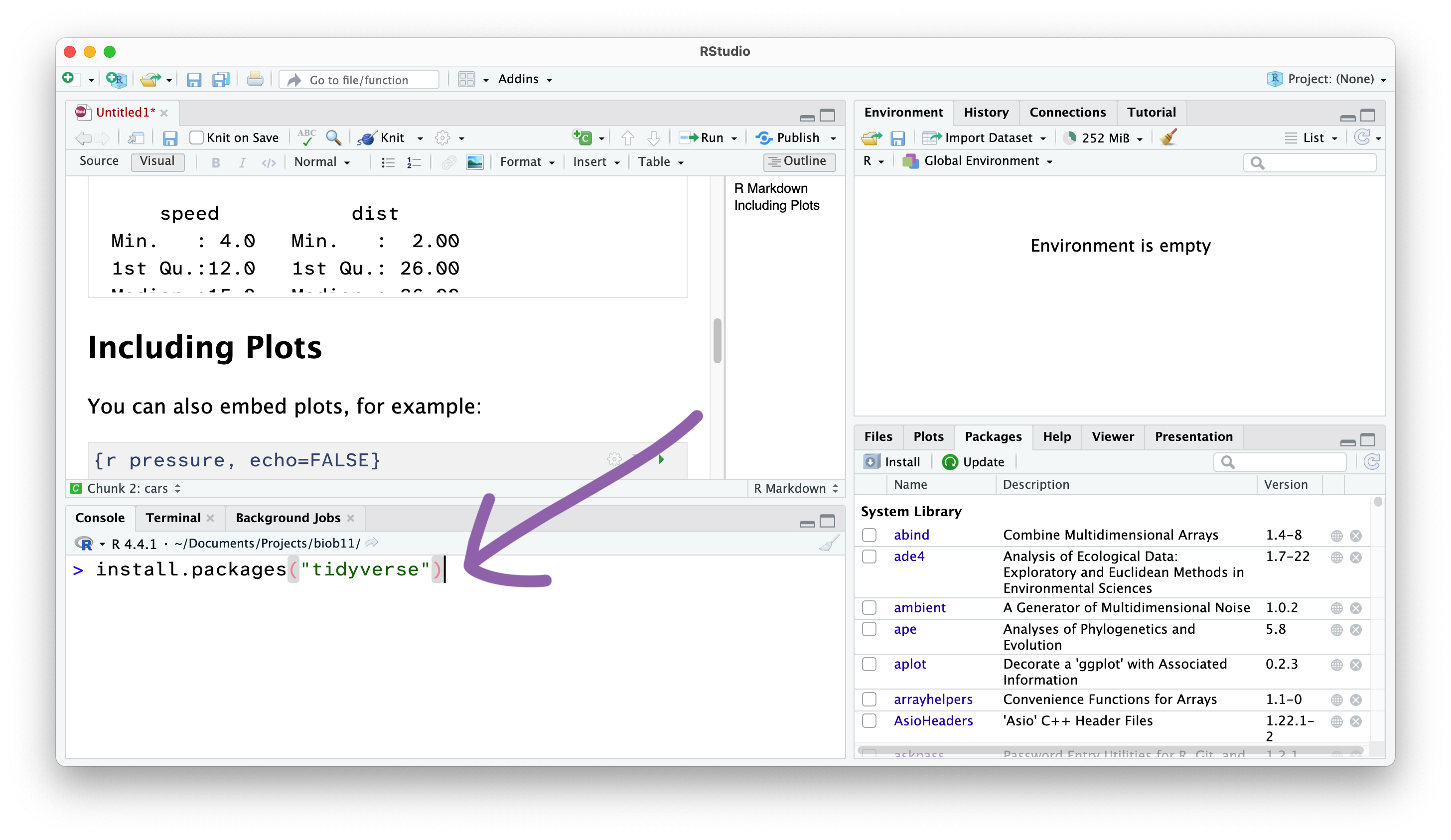

Installing R packages

In this exercise, we will use the tidyverse package, and the infer package. To install them you need to use the install.packages() function. Since we only need to do this once per computer, we should run this function directly in the Console panel.

Type or copy the install function into the console, and press enter to run:

From now on, we won’t write things directly in the Console, and instead write code in the RMarkdown document in the Source panel, which we then “Run” and send the Console.

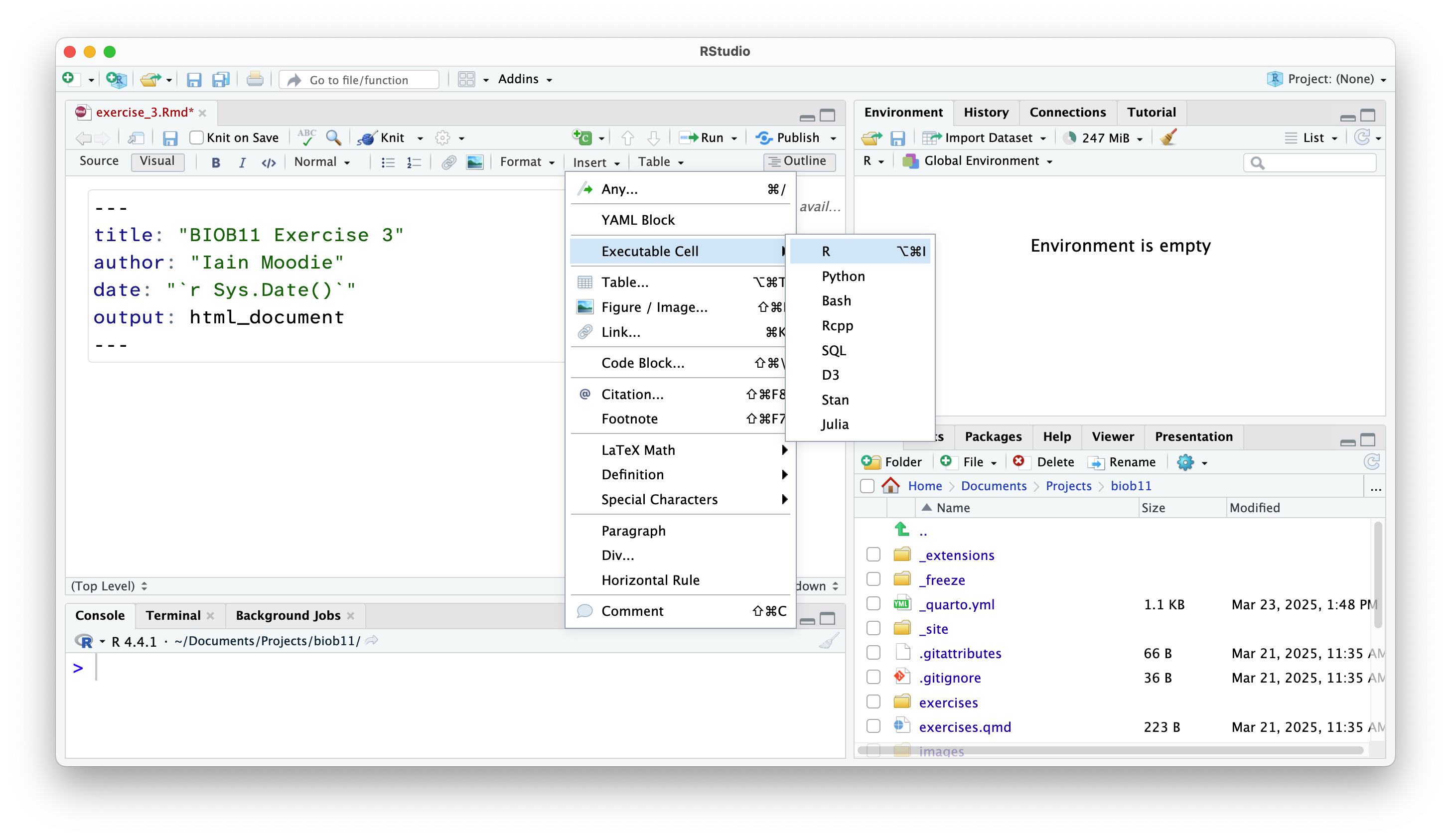

Creating code cells

Code cells are where we write code in an RMarkdown document. This allows use to write normal text outside these sections.

In your Source panel, in the RMarkdown document, add a R code cell. This is done in different ways depending on if you are using the visual view or the source view:

In both views, you can also use the shortcut Shift-Alt-I or Option-Command-I.

Loading R packages

After installing an R package, we need to tell R that we want to use the package in this document. We use the library() function to do that.

R code should always be executed “top to bottom”, so this bit of code should come right at the start.

Inside that code cell you just made, use the library() function to load the tidyverse and infer packages:

library(tidyverse)

library(infer)Then run the code. (To run code in the Source panel, you can click on the line you want to run, and then press the “Run” button. Or you can also use the keyboard shortcut Ctrl+Enter or Cmd+Return.)

If that worked, you will get a message that reads something similar to:

── Attaching core tidyverse packages ──────────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

✔ dplyr 1.1.4 ✔ readr 2.1.5

✔ forcats 1.0.0 ✔ stringr 1.5.1

✔ ggplot2 3.5.2 ✔ tibble 3.2.1

✔ lubridate 1.9.3 ✔ tidyr 1.3.1

✔ purrr 1.0.2

── Conflicts ────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errorsNot all packages produce a message when they are loaded (for example, infer did not).

Writing text alongside code

Anywhere outside a code cell you can write normal text. In this course, you might find it helpful to write yourself notes alongside your code, so that you can come back to your notes during other exercises, or later in your studies.

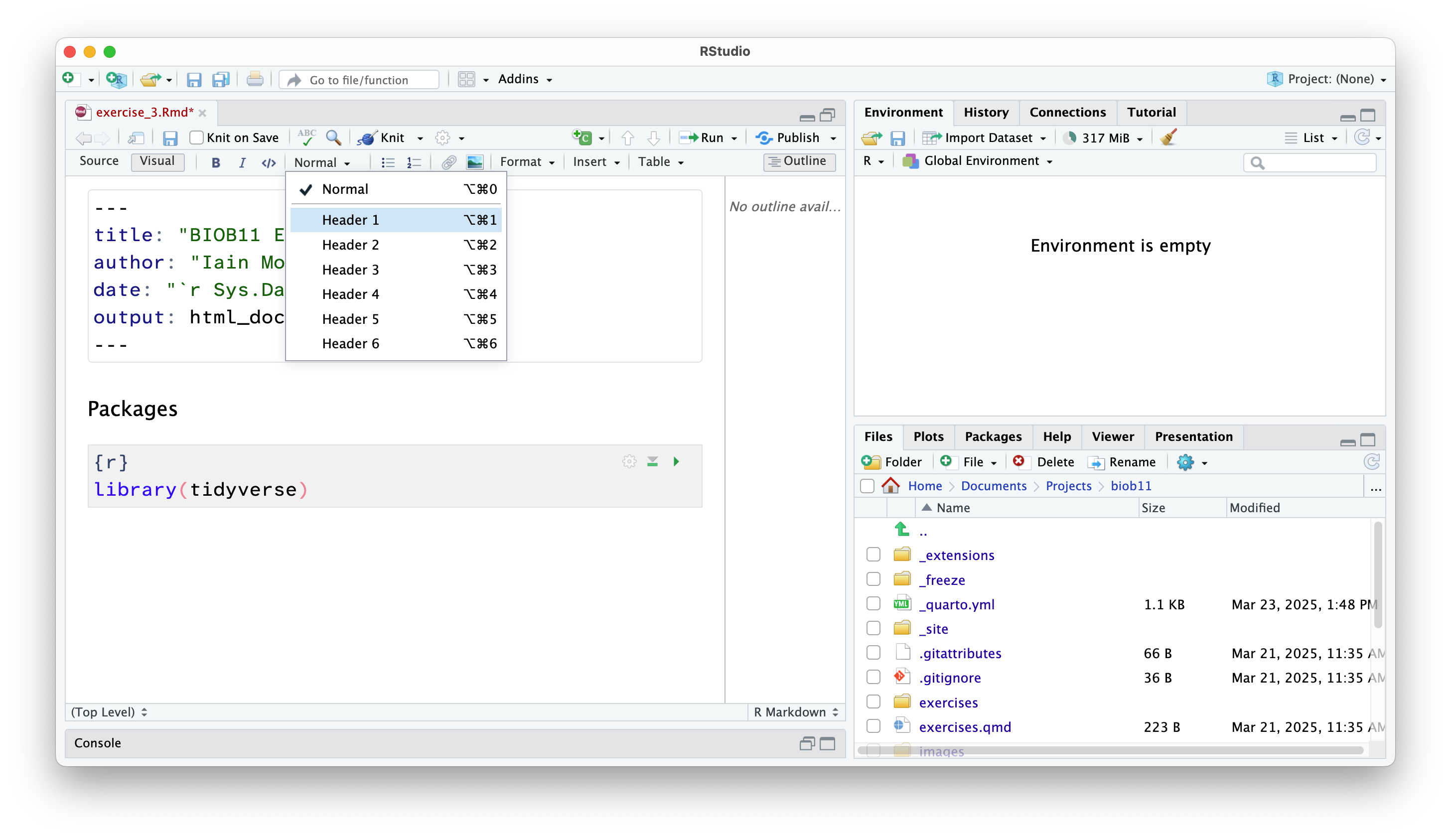

Along side normal text, you can structure an RMarkdown document using headings.

I leave it up to you to decide how and when to use headings and text.

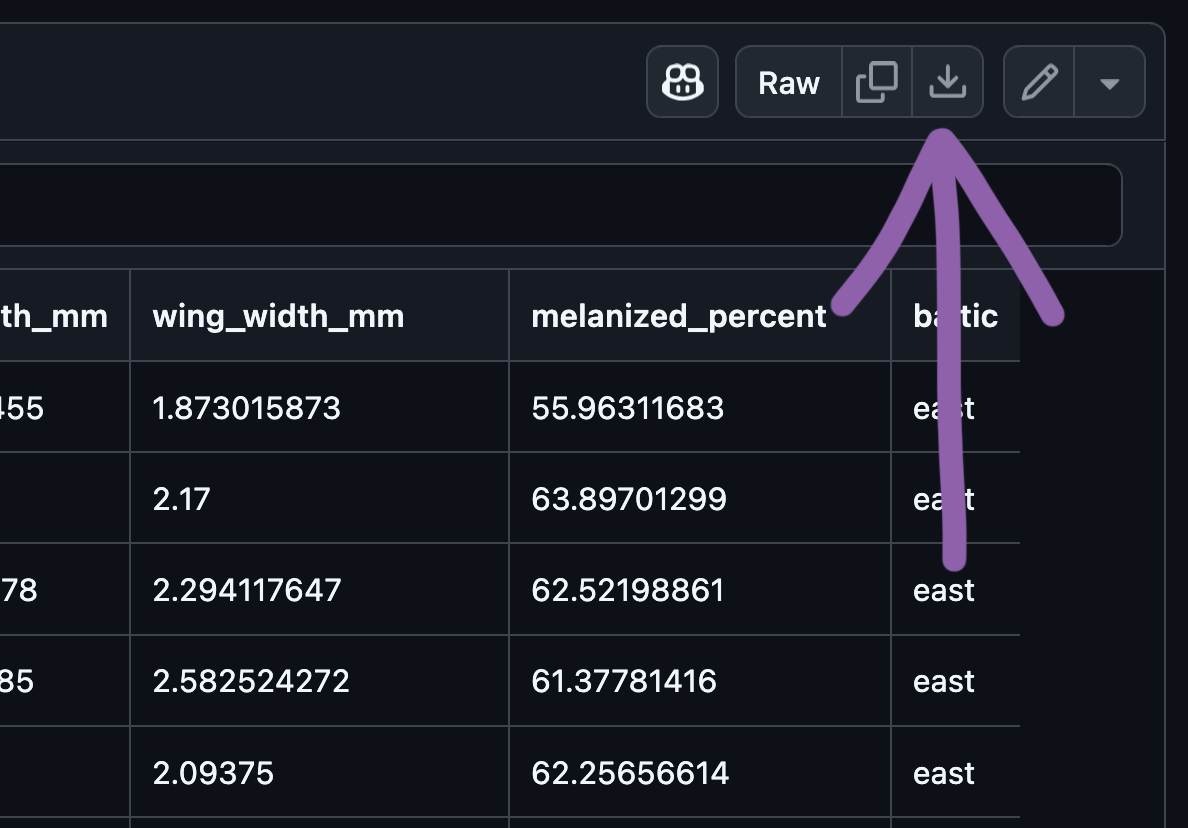

Importing data into R

We will now load the tephritis_phenotype.csv data file that you downloaded earlier. A .csv file is a file that stores information in a table-like format with Comma Separated Values. A typical .csv file will look something like this:

species,height,n_flowers

persica,1.2,12

persica,1.5,18

banksiae,2.4,3

banksiae,1.7,8.csv files are especially suited to storing data that can be used across a wide variety of programmes, as everything is stored as plain text.

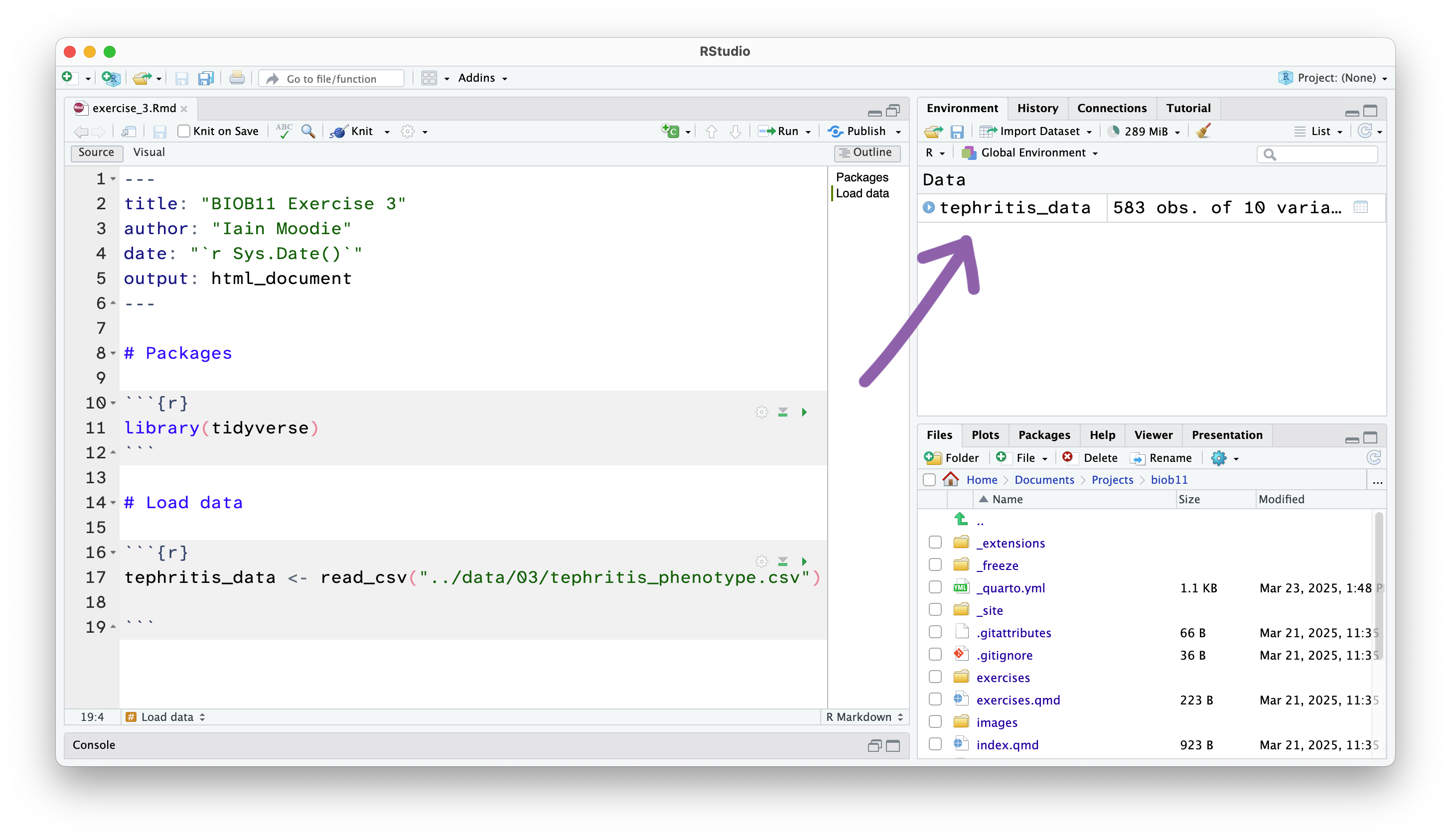

We will load the tephritis_phenotype.csv data file using the read_csv() function and assign it to an object named tephritis_data. To do that, first make a new code cell, then within it write:

1tephritis_data <- read_csv("tephritis_phenotype.csv")- 1

- Be sure to use quote marks around the file name.

If that worked, you should get the following message with some information about the data:

Rows: 579 Columns: 10

── Column specification ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Delimiter: ","

chr (5): region, host_plant, patry, sex, baltic

dbl (5): body_length_mm, ovipositor_length_mm, wing_length_mm, wing_width_mm...

ℹ Use `spec()` to retrieve the full column specification for this data.

ℹ Specify the column types or set `show_col_types = FALSE` to quiet this message.This has loaded a copy of the data from tephritis_phenotype.csv into R. Notice that the object tephritis_data has also appeared in the Environment panel.

To view the data, click on the object tephritis_data in the Environment panel with your mouse.

This allows you to view the dataset like you would in a spreadsheet software like Microsoft Excel. Note however, there is no way to edit the data in this view. This is by design. Any editing of the data needs to be done in the RMarkdown document with code. That way, you can keep a record of any edits you make, without touching the original data file.

Exploring data

Let’s use a few more functions to get a better understanding of the dataset.

Make a new code cell, and write the following:

1print(tephritis_data)- 1

-

We can also just simply write

tephritis_datawithout the print statement, and we would get the same output.

Let’s unpack what has appeared in your console:

- The first line of the output is telling us what sort of data is in the object. In this case, its a

tibble, a way of storing data in a table/spreadsheet format. - That same line tells us the number of rows (

579) and number of columns (10) in the table. - The next line tell us the variable types.

- Then the first 10 rows of the dataframe have been printed, along with the column (variable) names at the top.

- Below that, we get two important pieces of information, denoted by the small

ℹsymbol:- The first

ℹtells us how many rows are not being shown here. Since by default 10 are shown, \(579-10=569\). - The second

ℹtells us how many columns (variables) are not being shown here, as there was not enough room to print them.

- The first

- We can also see that some rows have

NAvalues (not applicable). This is the symbol R uses to say no data present.

Let’s use a few other ways of viewing our data in the console:

Make a new code cell, and write the following:

glimpse(tephritis_data)glimpse()transposes the dataframe, with columns now running down the page. This view means we can see all the variables.

You can also use summary() to calculate some useful summary statistics of the dataset as a whole:

Make a new code cell, and write the following:

summary(tephritis_data)Answering a research question

One of the questions that Nilsson et al. (2022) were interested in was if there has been any morphological (size of body parts) divergence between the host races of these flies. In other words, do flies that use "heterophyllum" as a host_plant and flies that use "oleraceum" as a host_plant differ in some predictable way?

Let’s use the variable ovipositor_length_mm to explore this research question.

Filtering the dataset

First, we should filter() our dataset to only contain females (as only females have an ovipositor). filter() is a function that let’s us write conditional statements that only allow rows that meet those conditions to “filter” through. For example, we can use filter() to only allow rows where sex == "female" to filter through, thereby creating a new dataset of just female flies.

Now we have the rows we are interested in, let’s move on.

Exploratory plot

Often before we start any formal statistics, we want to plot our data.

R has a built in method to make plots, but here we will use a different approach. Instead we will use ggplot2, a plotting package that is installed with tidyverse. ggplot2 provides a clear and simple way to customise your plots. It is based in a data visualisation theory known as the grammer of graphics (Wilkinson 2013).

The grammer of graphics gives us a way to describe any plot.

A ggplot2 plot has three essential components:

data: the dataset that contains the variables you want to plotgeom: the geometric object you want to use to display your data (e.g. a point, a line, a bar).aes: aesthetic attributes that you want to map to your geometric object. For example, the x and y location of a point geometry could be mapped to two variables in your dataset, and the colour of those points could be mapped to a third.

ggplot2 uses a layered approach to the grammer of graphics. This makes it very easy to start contructing plots by putting together a “recipe” step-by-step. Let’s walk through an example.

In our case, we want to plot ovipositor_length_mm for each host_plant group. One example might be a boxplot:

ggplot(

1 data = female_data,

2 mapping = aes(x = host_plant, y = ovipositor_length_mm)

3 ) +

4 geom_boxplot()- 1

-

Inside the

ggplot()function, I specify the dataset asfemale_data - 2

-

I map the

host_plantcolumn to the x axisaesthetic and theovipositor_length_mmto the y axisaesthetic. - 3

-

To add layers to a

ggplot()object, we can use a+ - 4

-

I add a boxplot

geometry, that will use theaesthetics I specified before.

Copy the code into a new code cell and run it.

Calculating the observed statistic

Our research question is:

- Do flies that use

"heterophyllum"as ahost_plantand flies that use"oleraceum"as ahost_plantdiffer in theirovipositor_length_mm?

The question concerns a difference in a continuous variable between two groups (host_plant). Let’s start by exploring if there is a difference in the central tendancy of ovipositor_length_mm in the two groups. That is, does average ovipositor_length_mm differ between them?

A suitable statistic that captures our question could be a difference in means.

\[ \bar{x}_{\text{heterophyllum}} - \bar{x}_{\text{oleraceum}} \]

We are going to do that using the infer package we loaded at the start.

To use infer to calculate an observed statistic, we use the approach we covered in the lecture:

In code, that looks like this:

4obs_stat <-

1 female_data |>

2 specify(response = ovipositor_length_mm, explanatory = host_plant) |>

3 calculate(stat = "diff in means", order = c("heterophyllum", "oleraceum"))- 1

-

Using the dataset we just made, we pipe

|>it into the next line. - 2

-

We

specify()which columns we are interested in, and which is our response variable, and which is our explanatory variable. In this case, we want to explainovipositor_length_mmusinghost_plant, and express that as a"diff in means". - 3

-

We

calculate()our chosen statisitc"diff in means", and we say that the subtraction should be"heterophyllum"minus"oleraceum". - 4

-

We assign this to a new object called

obs_stat.

Use the code above in a new code cell to calculate the observed statistic.

To see your observed statistic, simply print it by writing the name of the object.

obs_statQuantifying uncertainty

If we took another sample (that is, if we repeated the field work that Nilsson et al. (2022) did), it is unlikely that we would get exactly the same observed statistic, just due to chance. We want to quantify this effect. In this exercise, we will use a 95% confidence interval to do that.

We have already calculated our observed statistic, so let’s generate a sampling distribution using bootstrapping.

Recall from the lecture that a bootstrap sample is generated from the original dataset by resampling (randomly selecting rows) it with replacement (we can select the same row more than once). To complete one bootstrap sample, we resample with replacement until we have the same number of rows of data that were in our original dataset.

We then calculate our observed statistic using the bootstrap sample. This can then be repeated many times to construct a sampling distribution, which show the range of statistics we think it would be possible to observe, if we had actually sampled our population again.

To do that in code, we write the following:

2sampling_dist <-

female_data |>

specify(response = ovipositor_length_mm, explanatory = host_plant) |>

1 generate(reps = 10000, type = "bootstrap") |>

calculate(stat = "diff in means", order = c("heterophyllum", "oleraceum"))- 1

- Notice how this is almost identical to the code we used to get the observed statistic, but we have one extra step, where we generate 10000 bootstrapped datasets, then calculate the diff in means for all of them.

- 2

-

We assign this to a new object, called

sampling_dist

Use the code above in a new code cell to get a bootstrap sampling distribution.

Again we can print it by just writing its name:

sampling_distinfer has a helpful function to quickly see the distribution:

visualize(sampling_dist)Confidence intervals

We can use the percentile method to calculate a confidence interval. To do that we take the middle 95% of the bootstrapped sampling distribution. Again, infer has a helpful function to do this for us.

Use the code below in a new code cell to calculate your confidence interval.

conf_int <-

get_confidence_interval(sampling_dist, level = 0.95, type = "percentile")Again, print the object to see the confidence intervals:

conf_intWe can also visualise the confidence interval on our sampling distribution:

visualize(sampling_dist) +

shade_confidence_interval(endpoints = conf_int)Hypothesis testing

While our confidence interval is one way to address this question, we can also address it through “null hypothesis testing”. A null hypothesis test tests if flies that use "heterophyllum" as a host_plant and flies that use "oleraceum" as a host_plant differ in their ovipositor_length_mm more so than is expected by chance.

To do that we need to construct a null and alternative hypothesis.

A null hypothesis posits that the explanatory variable we test does NOT affect our data. We then test if our data is sufficiently different from the null hypothesis such that we can reject it.

A null hypothesis does not have be defined by a “zero effect”.

Opposite of the Null hypothesis (the explanatory variable affects our data). We normally think in terms of an alternative hypothesis

Generating data assuming the null hypothesis is true

As we did in the lecture, we will use a shuffling or permute method of creating a sampling distribution compatible with our null hypothesis.

To do that with infer, the code looks like this:

3null_dist <-

female_data |>

specify(response = ovipositor_length_mm, explanatory = host_plant) |>

1 hypothesise(null = "independence") |>

2 generate(reps = 10000, type = "permute") |>

calculate(stat = "diff in means", order = c("heterophyllum", "oleraceum"))- 1

-

Again, the code looks very similar, but now we have added an extra

hypothesise()step, where we declare our null hypothesis to be that theresponseandexplanatoryvariables are independent of each other. - 2

- We generate 10000 permutated datasets under this hypothesis, and calculate the statistic for each dataset

- 3

-

Save as an object called

null_dist

Use the code above in a new code cell to simulate a null distribution.

You can print by writing the name:

null_distThe same command as we used before for the bootstrap sampling distribution can be used to visualise your null distribution. Use visualise() to show your null distribution.

Visualising and calculating a p-value

Recall that we want to answer the following question:

Are flies that use

"heterophyllum"as ahost_plantand flies that use"oleraceum"as ahost_plantdiffer in theirovipositor_length_mmmore so than is expected by chance?

To help answer it, we can calculate and visualise a p-value, which is a probability of observing our original statistic, or one more extreme, assuming the null hypothesis is true.

Using our null distribution, we can take our definition above, and simple count the number of times we found an absolute difference in mean as great (or greater than) our observed test statistic, and divide that by the total number of statistics in our null distribution:

\[ p = \frac{\text{Number of times } |\text{null statistic}| \geq |\text{observed statistic}|}{\text{Total number of null statistics}} \]

This is a two-sided p-value.

In a new code cell, calculate the p-value using the code below:

null_dist |>

1 get_p_value(obs_stat, direction = "two-sided")- 1

- Since we did not have a reason to think one particular host race would be bigger, we use a two-sided hypothesis test.

We can also visualise the p-value on the null distribution, to get a better idea of where that value comes from:

visualise(null_dist) +

shade_p_value(obs_stat, direction = "two-sided")End of exercise.